Back in 2021, we wrote about a motion for a temporary restraining order (TRO) by an accused infringer in an attempt to force a patentee to undo its efforts to prevent the sale of the accused infringer's products on Amazon.

(We didn't do a subsequent update, but in that case the Court ultimately denied the TRO for failure to prove a likelihood of success on the merits. See EIS, Inc. v. Intihealth GER GmbH, C.A. No. 19-1227-LPS, D.I. 156 (D. Del. Dec. 10, 2021).)

In that post, I wondered why we don't see this issue come up more often. This week, the issue came up again. The accused infringer in Shanghai Qianzhuo Network Technology Co., Ltd. v. Cattasaurus, LLC, C.A. No. 25-830 (D. Del.) filed a TRO seeking to prevent the patentee from sending infringement complaints to Amazon.com. D.I. 13 at 2.

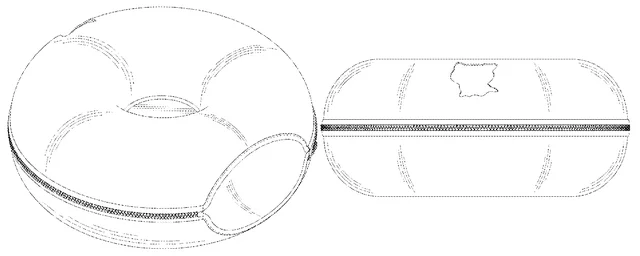

The case involved a design patent on a cat bed. The accused infringer claimed that their product exactly matched a prior art product, that it lacked a feature shown in the design patent, and that the patentee had contacted them "boasting about its past success in asserting infringement on Amazon against competitors." Id. at 1, 3-5.

The Court denied the motion just three days after it was filed, and before the patentee had even responded. The Court noted that "practicing the prior art" is not a defense to infringement:

FutureDiamond first argues that its accused products cannot infringe the #404 patent because the accused products are identical to a Chinese patent that is prior art to the #404 patent, and "prior art ... cannot be deemed infringing." . . . FutureDiamond does not cite any authority to support its contention that "[s]ince [FutureDiamond's] accused products are identical to the prior art, [FutureDiamond' s] accused products cannot infringe on the claimed design in the [#]404 patent." . . . In fact, the Federal Circuit has stated that "the defense of noninfringement cannot be proved by comparing an accused product to the prior art." Zenith Elecs. Corp. v. PDI Commc 'n Sys., Inc., 522 F.3d 1348, 1363 (Fed. Cir. 2008). "[A]ccused infringers are not free to flout the requirement of proving invalidity by clear and convincing evidence by asserting a 'practicing prior art' defense to literal infringement under the less stringent preponderance of the evidence standard." Tate Access Floors, Inc. v. Interface Architectural Res., Inc., 279 F.3d 1357, 1367 (Fed. Cir. 2002); see also Zenith, 522 F.3d at 1363 ("[M]ere proof that the prior art is identical, in all material respects, to an allegedly infringing product cannot constitute clear and convincing evidence of invalidity.").

Id. at 3-4. The accused infringer also argued that it could not infringe because it was missing a cat-shaped cutout, which is part of the claimed design. The Court also rejected that idea:

FutureDiamond also argues that its products do not infringe the #404 patent because " no reasonable finder of fact could confuse one for the other." D.I. 11 at 10. FutureDiamond points to a second opening disclosed in the #404 patent-an opening that is absent from the accused products. . . . Two designs are substantially the same [and a design therefore infringes] if "the resemblance is such as to deceive" an "ordinary observer, giving such attention as a purchaser usually gives," "inducing him to purchase one supposing it to be the other." . . .

Having looked at photographs of FutureDiamond' s accused products and the design disclosed in the #404 patent, I do not agree that " it is readily apparent" that the #404 patent's design and the accused products are "plainly dissimilar." . . . Given the shape, hole opening, and zipper placement of the claimed design and the accused products, it appears to me that an ordinary observer would purchase FutureDiamond's accused product "supposing it to be" the design disclosed in the #404 patent. Gorham, 81 U.S. at 528. FutureDiamond therefore has not made a clear showing that it is likely to succeed on the merits.

Id. at 4-5. The Court noted that it appears to the judge that the test for infringement is met. I'm not sure this will be preclusive of anything in the case, but I'm sure the accused infringer would prefer not to have that in the record.

The Court also found no irreparable harm:

FutureDiamond has not demonstrated, for example, that it faces an immediate, irreparable threat of suspension of its products listed on Amazon. FutureDiamond's only source of support is the Declaration of Chuanpeng Ning, the manager of Shanghai Qianzhuo Network Technology Co., Ltd. . . .That declaration merely states that "Cattasaurus LLC contacted FutureDiamond to boast about its past success in asserting infringement on Amazon.com against competitors and taking competitor[s'] listings down." . . . But FutureDiamond does not otherwise describe the specifics of this "boast[ing]." Nor does FutureDiamond identify any other actions that Cattasaurus has taken to threaten FutureDiamond. FutureDiamond also has not shown how Amazon's removal of its listings would cause it irreparable harm in the form of an "[i]nability to fulfill customer orders."

Id. at 6.

Ultimately much of the memorandum order is particular to the facts of the case and the way the issues were briefed. Still, I imagine it will be cited in opposition to future attempts by accused infringers seeking a TRO to head off threats involving sales on Amazon.com.

Beyond that, the fact that it was denied with lightning speed, before a responsive brief was even filed, shows something as well. If you are going to bring a TRO, it had better be well supported and carefully briefed.

If you enjoyed this post, consider subscribing to receive free e-mail updates about new posts.