Judge Burke issued a fascinating invalidity decision yesterday in Immervision, Inc. v. Apple, Inc., C.A. No. 21-1484-MN-CJB (D. Del.). It addresses an invalidity issue I had honestly never seen litigated—a "'single means' claim"—and, along the way, it addresses what a claim "element" is and when the "clear and convincing" standard applies to invalidity.

Basically, the whole thing is a page-turner for someone who deals with these issues, and well worth reading. I'll outline some of the most interesting points below.

"Single Means" Invalidity Is a Thing

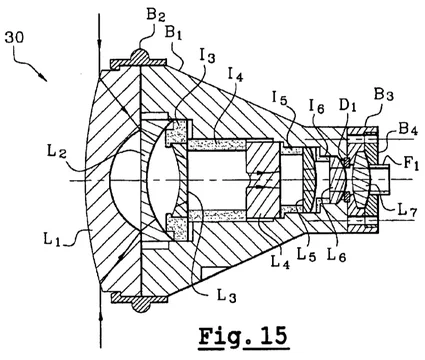

The invention at issue is an optical lens. The opinion involves an independent claim that claims a "panoramic . . . lens" that includes an "optical means" with various characteristics written out in functional terms (for example, that the lens projects an image with an expanded zone and a compressed zone), and a dependent claim that adds some additional functional limitations.

The opinion goes through some of the history and dusts off some really old opinions to explain why a "single means" claim is invalid:

Historically, the Supreme Court of the United States has been skeptical of and has prohibited broad functional claiming. See O’Reilly v. Morse, 56 U.S. (15 How.) 62, 113 (1853); see also Halliburton Oil Well Cementing Co. v. Walker, 329 U.S. 1, 12 (1946) . . . . That is, the Supreme Court refused to permit patent claims when the patentee used functional language in order to claim any means of accomplishing a result untethered to the “process or machinery [by which] the result is accomplished.” Morse, 56 U.S. (15 How.) at 113. . . .

That said, in enacting pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. § 112, ¶ 6 (“Section 112, paragraph 6”)—now 35 U.S.C. § 112(f)—Congress did permit patentees to express a claim in terms of its function. But it did so only in certain limited, narrow circumstances. Section 112, paragraph 6 recited as follows:

["]An element in a claim for a combination may be expressed as a means or step for performing a specified function without the recital of structure, material, or acts in support thereof, and such claim shall be construed to cover the corresponding structure, material, or acts described in the specification and equivalents thereof.["]

35 U.S.C. § 112, ¶ 6.

Immervision, Inc. v. Apple, Inc., C.A. No. 21-1484-MN-CJB, at 6-7 (D. Del. July 25, 2025).

The entire "single means" doctrine seems to turn on the words "for a combination" in § 112 ¶ 6. As the opinion explains, you can't have a means claim that covers the only claimed "element" in the invention:

So, what is a “single means” claim and why might such a claim be invalid for lack of enablement? As was noted above, Section 112, paragraph 6’s text states that means-plus-function language may be utilized to express “an element in a claim for a combination[.]” 35 U.S.C. § 112, ¶ 6 (emphasis added). In other words, Section 112, paragraph 6 allows means-plus-function-type claiming only as to claims that have more than one element; if the claim at issue contains only a single element (and not a combination of elements), then it does not meet the full requirements of this portion of the statute.

Id.

So it sounds complicated, but really it's just that if you have a claim with one "element," it can't be claimed using § 112 ¶ 6 language.

Here, the Court walked through the claims at issue and the law, and found that the single asserted claim was invalid because it included only a single "element," and it claimed that element using § 112 ¶ 6 language.

The Word "Element" Has Multiple Meanings in Patent Law

Patent litigators and courts often use the word "element" or "claim element" interchangeable with "limitation" or "claim limitation" to describe parts of a patent claim.

But, as the Court outlined here, "element" has another meaning in patent law: a mechanical element of an invention. That's the one that applies for the "single means" analysis:

In the Court’s view, when Section 112, paragraph 6 refers to an “element” in the context of an apparatus claim, it is referring to a mechanical element of the apparatus. The Court thinks this is so in part because P.J. Federico, a principal author of the 1952 Act and then-Chief Patent Examiner, explained in a contemporaneous commentary that as to this paragraph, “a combination may not be only a combination of mechanical elements [in an apparatus claim], but also a combination of substances in a composition claim, or steps in a process claim[.]” . . . With that said, the Court acknowledges that the Federal Circuit has noted that the term “element” can sometimes be used in patent law not only to connote “structural parts of the accused device or a device embodying the invention[,]” but also simply to refer to any limitation in a claim. Perkin-Elmer Corp. v. Westinghouse Elec. Corp., 822 F.2d 1528, 1533 n.9 (Fed. Cir. 1987).

Id. at 11-12 n.9. The opinion ultimately holds that the claimed lens (an embodiment of which is pictured above) is a single "element" such that the single means rule applies.

The "Clear and Convincing" Evidentiary Standard Doesn't Apply to Determinations of Law, Even for Invalidity

The Court noted at length that it did not have to apply the clear-and-convincing-evidence standard here, because it is dealing with an issue of law:

The Court certainly agrees with Plaintiff that the '990 patent enjoys the benefit of the presumption of validity, as the USPTO “has already examined whether the patent satisfies ‘the prerequisites for issuance[.]’” . . . But with regard to the motion at issue here, the parties’ disputes are not disputes of fact. They are disputes over questions of law. . . . That is, the Court is being called on to assess whether claim 21 is a “single means” claim, which is an issue decided solely in light of the relevant claim language. . . . Since the Court need resolve only disputes of law in addressing this dispute, the clear and convincing evidence standard will not be applicable to its decision here. . . . Put differently (and as will be seen below), Plaintiff has not plausibly suggested the existence of disputed factual issues that have relevance to the resolution of the Motion for Judgment on the Pleadings. Therefore, the Court will adjudicate that motion simply by determining whether Defendant’s argument is correct as a matter of law, without importing any evidentiary standard of proof into that analysis.

Id. at 10-11.

This comes up with fair frequency, and it is a good point to keep in mind. The clear-and-convincing standard simply doesn't apply if the Court is making a pure determination of law.

"Single Means" Invalidity Is Fundamentally About Enablement, Not Claim Construction, And Need Not Be Raised at Markman

This issue came to the Court on a Rule 12(c) motion for judgment on the pleadings. The Court rejected an argument by the patentee that this is something that must be raised at the Markman stage:

Plaintiff also insists that the Motion for Judgment on the Pleadings should be denied because this “single means” claim issue should have been raised and addressed as part of the Markman briefing process. . . . The Court does not see why that is so. As noted above, the issue is one of law—and it is an issue that was properly invoked via a motion for judgment on the pleadings, which is a type of motion that a defendant is perfectly permitted to file. Moreover, herein the Court is not “construing” any particular term in claim 21—at least not in the sense that it is being called upon to resolve a dispute over the definition of a particular word or set of words found in that claim (or a dispute over whether a claim preamble is limiting). . . . Additionally, since the issue at play is lack of enablement, and since that issue is not typically addressed as part of the Markman process, . . . it makes total sense that Defendant did not raise it there.

Id. at 20 n.14.

If you enjoyed this post, consider subscribing to receive free e-mail updates about new posts.