Judge Andrews issued a lengthy summary judgment and Daubert opinion on Thurday in Acceleration Bay, LLC v. Amazon Web Services, Inc., C.A. No. 22-904-RGA (D. Del.). The opinion hits multiple interesting issues, and we may have a couple of posts on it this week.

But the one ruling that jumped out to me was the Court's rejection of the fairly typical, low-effort motivation-to-combine language that many experts rely on in their obviousness opinions.

Motivation to combine is often an afterthought. I've seen many initial contentions that address it only in a short paragraph that basically just lists characteristics of each reference (same field, same problem, etc.). Expert reports sometimes uncritically adopt paragraphs like that with no elaboration.

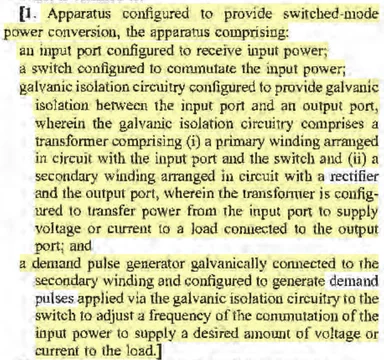

If you've ever been involved in reading or writing invalidity contentions, you've probably seen motivation-to-combine paragraphs just like this one, from Thursday's opinion:

As those charts show, [the first reference] ATT Maxemchuk builds upon [the second reference] ’882 Maxemchuk and informs a POSITA of additional details related to ’882 Maxemchuk’s grid-based mesh network. A POSITA would be motivated to combine these references for several reasons. Both references are in the network architecture field and are directed to improving mesh networks. Both teach the simplification of routing of data that arises from the grid-based mesh network. And both disclose the same grid-based mesh network. In addition, ATT Maxemchuk includes additional implementation details for the grid-based mesh network that ’882 Maxemchuk describes.

The paragraph gives just four one-sentence reasons for its statement that a person of skill in the art would combine the references. Three of the reasons are about general similarities between the references.

The fourth sentence is a bit more helpful, and says that the first reference provides "additional implementation details" for part of the second reference.

The Court found that this paragraph—which the parties agreed was representative—simply could not provide support for a motivation to combine the references. The Court granted summary judgment of no obviousness:

Mr. Greene “fails to explain why a person of ordinary skill in the art would have combined elements from specific references in the way the claimed invention does.” . . . His opinion does nothing more than explain why the prior art references are analogous to each other and to the claimed invention. . . . Plaintiff’s “assertions that the references were analogous art, . . . without more, is an insufficient articulation for motivation to combine.” . . .

As Defendant’s invalidity contentions rely on Mr. Greene’s testimony, Mr. Greene’s failure to opine on a POSA’s motivation to combine the asserted prior art references proves fatal to Defendant’s obviousness theory. I grant summary judgment of nonobviousness as to all asserted obviousness defenses.

Acceleration Bay, LLC v. Amazon Web Services, Inc., C.A. No. 22-904-RGA, at 37-38 (D. Del. Sept. 12, 2024).

Judge Andrews also rejected the argument that other paragraphs or the charts themselves supported a motivation to combine:

Despite indicating paragraph 149’s representativeness, Defendant maintains that other paragraphs of Mr. Greene’s report, such as paragraph 151, and claim charts cited in the report “go beyond” paragraph 149. . . . These paragraphs add nothing in terms of demonstrating motivation to combine. The paragraphs that come closest to discussing motivation to combine refer to “common problems and challenges addressed by the references” or “improvement[s] described in one of these references [that] can be readily applied to the operation of another reference’s description.” . . . These generic and unspecified motivations are insufficient. See Intel Corp. v. Qualcomm Inc., 21 F.4th 784, 797 (Fed. Cir. 2021) (noting that motivations to combine are legally insufficient where they are asserted in a generic, conclusory manner). The claim charts, which do little more than identify relevant portions of each prior art reference, likewise do not describe any motivation to combine the references.

Id. at 38 n.21.

It's clear that you need something more than a list of similarities to justify an obviousness combination.

Sometimes, however, lengthier motivation-to-combine analyses can be risky. One the one hand, you have the danger that the Court will find the disclosure insufficient (like the above). On the other, there is a risk that, if you do a more elaborate motivation-to-combine paragraph, you will give the opposing expert ammunition to use against you—not only as to those references, but also in other ways.

I remember a case years ago where our expert drafted what I thought was a great motivation-to-combine section, describing in very specific terms problems with the first prior art reference and exactly how and why a person of skill in the art would look to the second reference to address those problems.

The combination was a bit of a tough lift but we hoped a detailed motivation-to-combine paragraph could help.

Nope. Ultimately the combination still didn't quite hit the elements of the claims well enough. But our description of the problems with the prior art was so useful to the other side that it became one of their case themes ("defendant needed our invention to solve the problem of x, which it admits was an issue with prior art devices . . ."). That's no good.

So it's easy to see why parties may sometimes prefer short and vague motivation-to-combine paragraphs. But don't go so narrow that your entire obviousness case gets precluded at the SJ stage.

If you enjoyed this post, consider subscribing to receive free e-mail updates about new posts.