There is no more cliched legal advice than "say nothing." It is such a staple of the greater Law and Order cinematic universe that the average 8-year-old, upon being arrested for rampant tomfoolery (still a crime in Delaware!) knows to ask for their phone call and then remain silent.

Wow Tech USA, Ltd. v. EIS, Inc., C.A. No. 24-115-GBW (D. Del. Jan. 9, 2026) dealt with the fallout of an earlier patent dispute between the parties.

Both parties are competitors in the field of obscure and presumably advanced sex toys with "air pulse technology." The case had gone to trial in 2023, with the jury returning a verdict of willful infringement and awarding a $12.8 Million lump sum royalty (a running royalty was also an option on the jury form, so this lump sum choice was explicit).

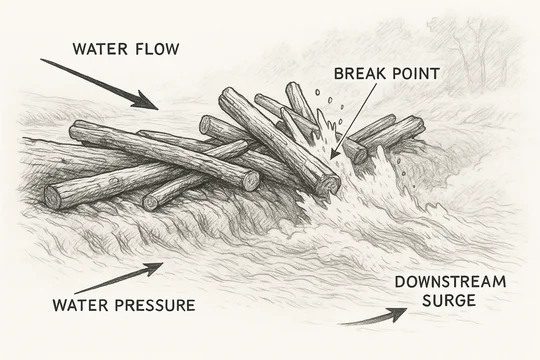

However, the defendant's equitable defenses were not decided at the trial and remain outstanding, and thus no final judgment has been entered.

This new case arose when the defendant allegedly told potential customers that:

the jury verdict in the Patent Action "gave Defendant a fully paid-up license for the lifetime of Novoluto's patents-in-suit," and that the license includes Defendant's Air Pulse products, "including new-yet-materially-identical products Defendant has released and continues to introduce to the market since trial in the Patent [Action]."

Id. at 2 (quoting complaint).

Plaintiff thus brought Lanham Act false advertising claims (along with a host of related state law claims) based on these statements and defendant moved to dismiss arguing that these statements were literally true because "[a] lump sum patent damages award has the same effect as a lifetime paid-up license to the patents."

The Court granted the motion to dismiss for lack of particularity in the allegations (taking a side in the Third Circuit split on ...